United Voice: The Wyoming Equality Magazine

June 2023 Issue

LGBTQ Expressions

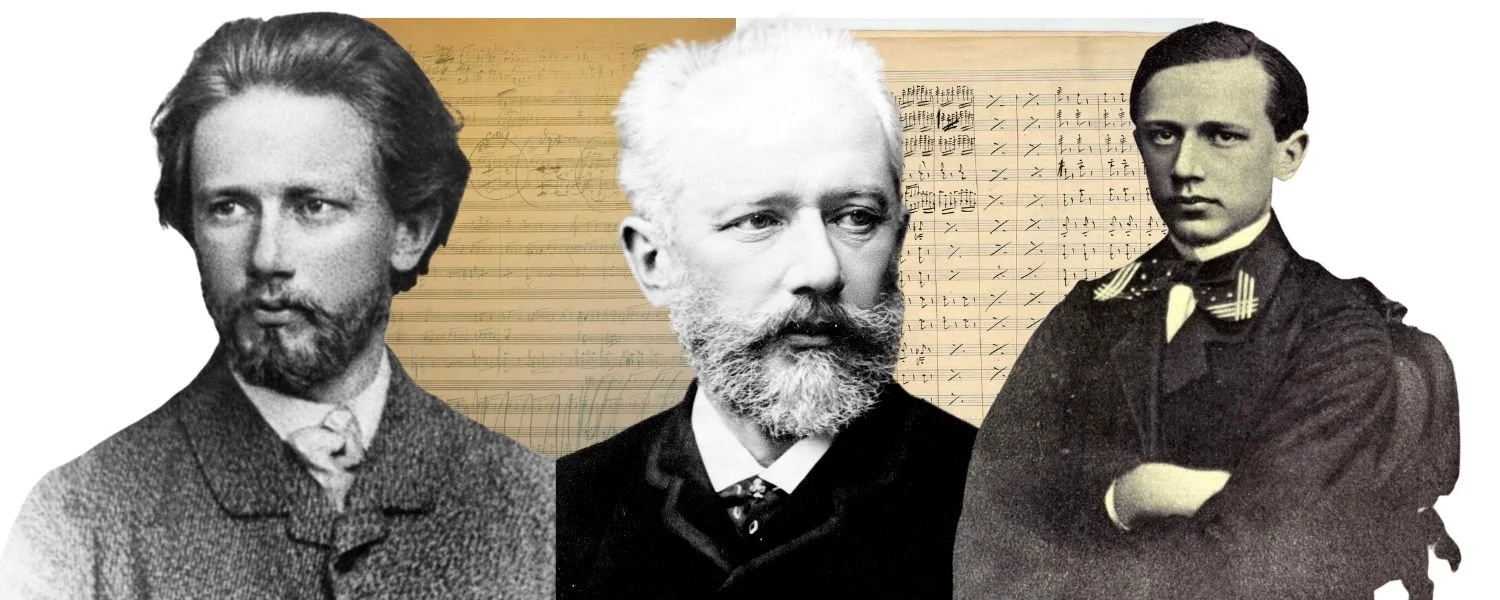

The Late, Great Tchaikovsky

A series exploring and celebrating queer creative greatness and legacy.

Essay by Daniel Galbreath

This piece references mental illness and suicidality.

I.

The composer Tchaikovksy just seems to keep cropping up in my life.

The first classical CD I ever bought, with my very own money, was entitled (unironically, to beggar all belief) Tchaikovsky’s Greatest Hits. Titles like this are for compendiums bought by my parents to revisit their youths. I did things in reverse, though. I bought the greatest hits of an artist who’d only later, gradually become an obsession. It’s hard to have nostalgia for an artist who died almost a century before I was born. So I started with the retrospective, and as I moved through my life, he came to feel more and more current.

Naturally, I started with the perfunctory shallowness that usually marks nostalgia, even when it’s turned ‘round the wrong way. The first piece of Tchaikovsky’s that I loved was big, and it was loud. Marche Slave (1876) rattled the house with its “exotic” bombast, and as a perennially Misunderstood Teenager, this suited me perfectly. (Frankly, I still get a kick out of it, and you probably will too. Cut yourself some slack in a busy day; indulge.)

II.

Marche Slave

Violin Concerto

I already had an inkling that I loved classical music - that I was one of “those people.” Marche Slave, more than any other work, cemented that initial impression.

But, of course, I also knew I was growing into my identity as another one of “those people.” That status as a Misunderstood Teenager was compounded by what promised to be a long-term closet residency. I was coming of age as a gay kid in Sheridan, Wyoming, and while there are some incredible people doing incredible work there now, in the 90s and early 2000s, it was a different story. I know it’s a cliche, but it was also very true: my gayness was shared with me and me alone.

Well, me, and Tchaikovsky. I like to think that I somehow knew that Tchaikovsky was gay before having it confirmed, but that’s probably not true. What probably happened was that a composer’s work resonated with me in a big way, and our similarly closeted lives under repressive regimes (if you’ll forgive my comparing Imperial Russia to Sheridan Junior High School at that time) felt like it explained that resonance.

(I’ll only pause momentarily to wearily acknowledge the debate still occurring over Tchaikovsky’s sexuality. Russian authorities continue to deny his homosexuality; the rest of the musical community now generally recognizes it. It is plainly clear that the former only hold their view out of homophobic authoritarian expediency.)

Now, being in the closet involves a lot of unrequited love. Adolescence in general does, even without the closet. So when I learned that his violin concerto, a piece I’d been listening to more or less on repeat, was possibly an expression of unrequited and unrequitable infatuation with a man nicknamed “Bob,” the significance of Tchaikovsky to my life only increased.

Of course, I don’t know if the concerto is a kind of closeted love letter. In any event, the primacy of what we “know” of a musical work and a composer’s “intentions” has been complicated and, ultimately, supplanted by recent musicology, which grapples with the simple truth that any musical work is about a lot more than any singular, originary intentions. (In fact, even those originary intentions have been complexified and trenchantly questioned, but if you want more on that you’ll have to read some Peter Kivy, which I’m not sure I can in good conscience recommend.)

What I do know is the effect that this piece has on me, starting at 7:25 of the recording above. Get a load of that tune! You’ll be humming it for weeks, and be better for it. The strings all join to “sing” the theme en masse like an anthem, and behind them, valedictory trumpets propel them forward. It’s sweeping, it’s gorgeous, and to me, it’s also deeply sad. The brilliant opening harmonies are soon clouded over by melancholy - you can hear it. To me, it’s the intense, almost desperate sense of resolve that only a counterbalancing grief brings.

The music then briefly retreats, wanders, questions itself…until the return of the violin.

The violin soloist plays that sweeping theme from before, but alone this time. There are notes added. It’s no longer heroic: it’s wistful, errant in an almost childlike way. Every embellishment quivers, smiles, sighs, pulls on the threads of desire. It’s a complicated, confused version of the theme that seems to dance with itself, stuck in the joy and sorrow of its own mind.

III.

Symphony No. 6

You may not have time to listen to the full Sixth Symphony. I’d find time, though (and crank the volume!). I found time in a busy summer work schedule, when I was about 21, by listening to pieces I was interested in while I ran late at night. I’d somehow not heard this symphony yet. The frenetic triumph and quirky rhythms of the first three movements made for an exuberant moonlit run through the empty streets of Laramie. Then came a slow hymn-dirge.

And then, no more sound came. Generally (though not universally), symphonies from the 1800s ended with triumph and glory. I thought there’d be one more movement, but this symphony ended by sinking into obscurity. Ten days after composing it, the composer died.

Much ink has been wasted in the debate over whether Tchaikovsky’s death at age 53 was deliberate or accidental; whether the funereal nature of his final work (funeral themes are laced throughout all four movements, I later learned) can give any insights into his frame of mind. He’d lost many friends in these later years of his life, and he was perennial preoccupied with death regardless. So, who knows?

I don’t, and I don’t need to. Once again, Tchaikovsky spoke to me at the right place at the right time. When I first came across this symphony, I was still reeling from an accident I’d been in a few years prior. The resulting brain injury and concomitant jostling of my mental health brought my preoccupations perilously in line with those of Tchaikovsky.

IV.

The late, the great…

Forgive me one more reference to musicology. (No one gets excited when they hear that word, do they? I’m sure it makes you think of dusty oddballs…just another set of “one of those” people.) A handful of recent musicologists have turned their attention to “lateness” - to what characterizes the final chapter(s) of a composer’s creative output. For Tchaikovsky, it was discipline, complexity, and sadness.

And it’s too late, now, for the late composer to reverse that. It strikes me with some sadness that it’s too late for him to live in a world that might have taken better care of him. But, would our world? The more I think about it, the more I think not. He was queer, he was mentally ill, and he was an artist. None of those are supported as much as they should be in our state and in our country, let alone his.

And in any case, it’s not too late for me, and for you, if I’ve got you hooked on him now. We can move from the utter dismay of the Sixth Symphony to the wit of the Rococo Variations, or to the craftiness of the Fourth Symphony, or to the maniacally joyful empowerment of the Fifth. We can leave the slavic intensity of the Marche for a holiday with Tchaikovsky in Florence (Souvenir de Florence) or stand in his company in awe before the divine (the Liturgy of St. John Chrystostom).

A whole lot more than the circumstances and intentions of a work’s initial creation matter to its meaning. Tchaikovsky’s life and work coincided to have great meaning for me at some of the more difficult points in my life. But it’s not too late for our friendship to have turned course, and for this friend to take on new meaning. No person - composer or listener - is just one thing. There’s room to hear the jollity in Marche Slave, the operatic opulence of the Violin Concerto, the serenity of the finale of the Sixth Symphony. Who needs nostalgia when Tchaikovsky stays with me, every day.